Robert Fripp and Gary Numan’s Journeys into Post-Punk

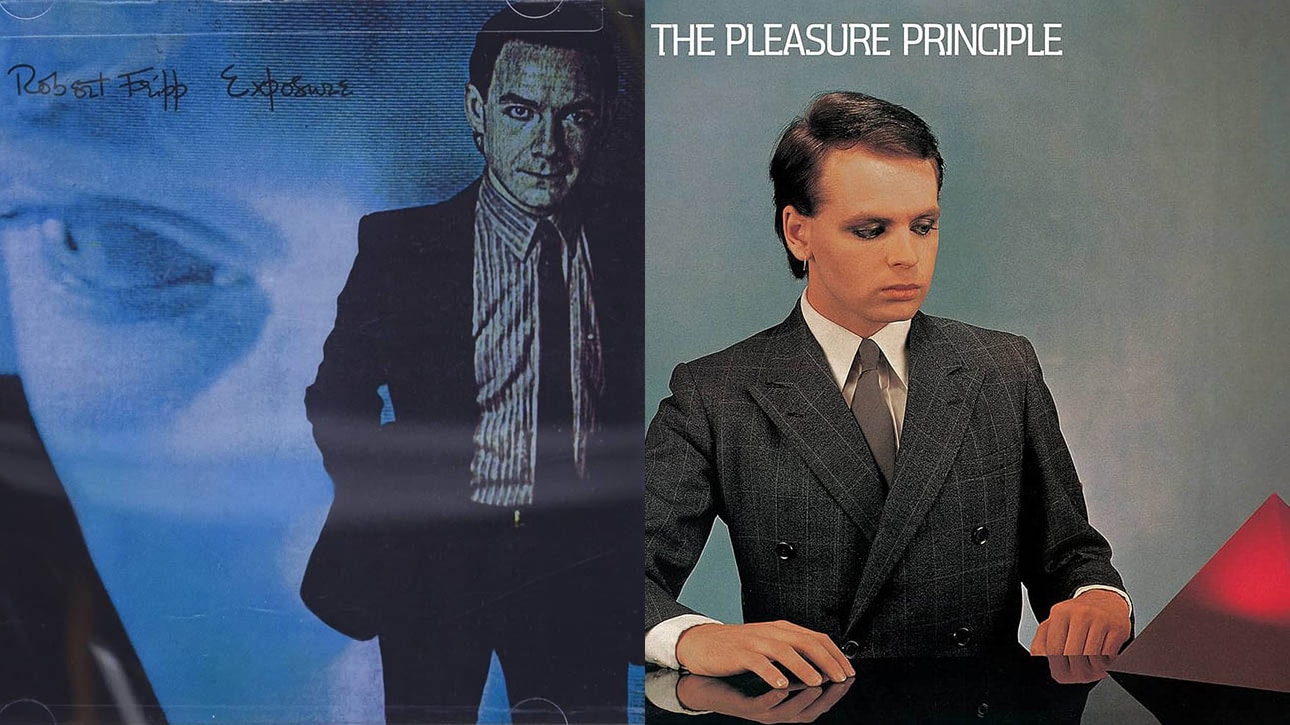

In the late 1970s, punk rock was headline news in the UK. In December 1976, a live broadcast television interview on The Today Show with the Sex Pistols stirred up “The Filth and the Fury”, a headline from the tabloid newspaper Daily Mirror, which was later borrowed for the title of Julien Temple’s 2000 Sex Pistols biopic. Inspired by the raw, malleable energy of punk, successive generations of music historians would cast this excitement as a cultural shakeup, declaring 1976 to be pop music’s “year zero” – a phrase that could be found in the 1978 EP Datapanik in the Year Zero by American art-punks Pere Ubu. Music critic and historian Simon Reynolds’ 2005 retrospective of the post-punk scene would summarise its mission to Rip It Up and Start Again, referencing the Scottish new wave group Orange Juice and their song “Rip It Up“. Punk rock had an irrefutable visceral appeal, but the portrayal of radical young upstarts pushing aside the dinosaurs of the past generation ignores how British bands have always been important to the development of rock culture. Yet while vintage British groups continued to have huge commercial fortunes at the end of the 1970s, they weren’t interacting much with their homegrown fanbase or domestic music industry. Supertramp‘s 1979 hit record Breakfast in America hinted at that band’s new home, touring and recording almost exclusively in the biggest market for popular music. Parts of The Wall, Pink Floyd’s statement of Roger Waters’ desire to build a literal wall between himself and his audience, were recorded in America and France, where some group members lived as tax exiles. Electric Light Orchestra would record 1979’s Discovery in Germany. There was another wing of the Anglophone rock music establishment seeking the solace of seclusion in Germany, who in 1977 collaborated on an unholy trinity of art rock albums awash with studio experimentation and electronic textures, resulting in David Bowie’s Low, Iggy Pop’s The Idiot, and Brian Eno’s Before and After Science – all released in 1977. Eno’s conceptual approach to music making, what he called oblique strategies, caught the attention of the culturati, who had otherwise no time for the crass, commercial business of popular music. A less prominent but even more prolific collaborator was Robert Fripp, who had been lurking in the shadows, sometimes quite literally, since disbanding King Crimson in 1974, and who in 1979 would release his first solo album, Exposure. Punk rock had a clear effect on the future sound of British rock, but it wasn’t the only new thing happening in popular music. Since the beginning, rock music has been based on the solid foundation of the blues. In the UK, the appeal of the blues to the 1960s beat music generation had grown from the novelty of acquiring records that had to be imported from a faraway land which told the stories of the blues singers who had been part of America’s Great Migration, listening amongst friends, and trading records at clubs devoted to the playing of the blues. To the music aficionados of the late 1970s, the sounds of Jamaican reggae and West African highlife, as well as the rebellious figureheads of Bob Marley and Fela Kuti, provided an alternative source of inspiration, and one that could be found closer to home in British reggae groups like Aswad and Matumbi. Along with the blues, rock music drew contemporaneous influence from the danceable exuberance of soul and funk, and now disco music was the latest dance craze. The co-productions of Donna Summer and the Italian producer Giorgio Moroder were created using synthesizers and drum machines. One of the most popular acts in Britain at the time was the Swedish group ABBA, whose hits often combined infectious melodies with irresistible disco-inflected beats. Music connoisseurs who were fans of David Bowie or Roxy Music might dig deeper into the world of European rock music and bands such as Kraftwerk and Can, who had been using electronic sound effects and hypnotic, mechanistic rhythms in rock music since the early 1970s. The influence of reggae, disco, and European rock was broad across British post-punk in 1979, with distinctive regional scenes and several independent enterprises in recording. In the West Midlands city of Coventry, the Specials combined social awareness and ska revival on their debut The Specials, recorded by the band’s own 2 Tone record label. The revered Manchester post-punk band Joy Division, whose original name was Warsaw, produced their debut Unknown Pleasures on Factory Records. Across the Pennine hills in Sheffield, the Human League launched with the all-electronic Reproduction, while fellow synthpop pioneer Gary Numan’s album The Pleasure Principle was released on Beggars Banquet Records (all released in 1979). The coming new decade of popular music was looking exciting. Let’s take a moment to look back further. The year 1979 was also the tenth anniversary of In the Court of the Crimson King, the debut album by King Crimson, the band with whom Robert Fripp is most closely associated. It also marked a decade since From Genesis to Revelation and Yes, the debut recordings by Genesis and Yes, who, with King Crimson, arguably formed the holy trinity of British progressive rock. By its progressive nature, the music of these bands had been continuously evolving, but In the Court of the Crimson King was clearly the most auspicious debut. Both From Genesis to Revelation and Yes dabbled in psychedelic pop, which paled in significance next to their subsequent works. In the Court of the Crimson King was an immediate success. The record harnessed the spirit of the 1960s while trailblazing for the upcoming decade. During the golden age of progressive rock in the early 1970s, the music was always epic and ambitious, but Genesis and Yes had a whimsical streak that was distilled in their use of words and visuals. The titles of Genesis songs and albums used archaic language and themes, matched by quaint album artwork and Peter Gabriel’s stage costumes. The titles of Yes songs contained many celestial allusions, matched with Roger Dean’s album artwork depicting broad skies and extraterrestrial landscapes. King Crimson’s frequently seemed more ominous and/or cerebral, as captured by the grotesque figure on the cover of In the Court of the Crimson King. Fripp was the closest to a figurehead of progressive rock, being the only continuous member of King Crimson. In 1973, he collaborated with Brian Eno on the album No Pussyfooting, when he developed his compositional technique “frippertronics” – using tape delays to build cascades of sound. This work also inspired his idea of”“small intelligent mobile units”, which explained King Crimson’s continuously revolving ensemble of relatively few musicians. By the end of the 1970s, King Crimson was no more. New releases from Genesis and Yes were conspicuously absent in 1979, as both bands were again altering their sound, streamlining their music as progressive rock fell out of fashion and the old guard sought to craft pop hits that would earn them commercial posterity. Starting in 1975, Robert Fripp took a sabbatical from music, disillusioned by the music business and his place within it. “One gets the feeling that the spirit of the late sixties has completely evaporated. It seems to be a thing when everyone was involved in trying to do something. But the mood now is completely different. There’s no magic in the air, or atmosphere from either the audience or the musicians. It’s a very uptight and unsettled situation, which, taking the broader picture of change in the world, it’s a very good example.” Fripp returned to music after satiating his worldly curiosity at the International Society for Continuous Education and, true to the spirit of In the Court of the Crimson King, was to chart an adventurous course through the currents of new wave music. His return was characterised by a series of adventurous and often unexpected collaborations. “I think that the music of the 80s is the music of collaboration. Increasing mobility between musicians is the key to the new music – whatever it is that anyone is trying to grasp in the sense of ‘The New Music.’” Fripp first worked with Peter Gabriel, contributing guitar and production ideas throughout Gabriel’s solo projects from 1977 and 1978 and performing in Gabriel’s promotional tours while hidden from view of the audience. Gabriel is, like Fripp, an overlooked figure. His early solo work was pitched nebulously between experimental and quirky new wave but with a lot of the pomp and drama of old-school progressive rock. Fripp more famously contributed his distinctive guitar tones to David Bowie’s 1977 album Heroes. Fripp was also motivated by his “drive to 1981”, a complex web of intrinsic motivations that would culminate in parallel with the extrinsic resolution of New Wave. “I see rock music as being a seven-year cycle, each rock generation has seven years. The first year is the Main Statement, then three years later, roughly the beginning of the fourth year, you have the second thrust, which is generally a better articulated, considered and well-rounded expression of the first statement.” In 1977, Fripp relocated to New York City, where he became enamoured with disco. Fripp’s pulsating guitar would set the tone of “Fade Away and Radiate“, the fourth track of Blondie’s 1978 album, Parallel Lines, in sharp contrast to the three sharp and bouncy power pop singles which opened the album. The following year, Fripp would partake in the polyphonic creation of “I Zimbra“, the opening track of Talking Heads’ 1979 album Fear of Music, a song that mixed disco and worldbeat influences that would be further developed for the Talking Heads’ landmark 1980 record Remain in Light. Credited as Fripp’s first solo album, Exposure is a meticulously plotted entry in the drive to 1981, which tidily synthesised his various conceptual preoccupations. The record offset its focus on new wave rock with hints of avant-funk and ambient Frippertronics, styles which Fripp planned to explore further in a series of dedicated albums. Each song is a small intelligent mobile unit of two to four minutes, played by a revolving cast of small intelligent mobile units. Fripp invited Debbie Harry to appear on the album, but Harry’s record company refused due to Blondie’s rising commercial star. In Fripp’s most leftfield partnership, he and Daryl Hall of Hall & Oates recorded two music albums together in 1977. Hall’s record company refused to release Hall’s Sacred Songs until 1980 and requested that Hall’s vocals be removed from all but two of the songs on Exposure due to its commercially unpalatable music. What could be more punk than that? The record opens with the monologue: “Could I play you some of the new things I’ve been doing, which I think could be commercial?” Despite Fripp’s conceit that the year 1981 would complete his celebrated return to the music marketplace, there isn’t a lot of pure pop on Exposure. Instead, there were concise compositions driven by exciting collaboration and dextrous performances. The album’s most familiar tracks sound like classic British hard rock. The first song proper, “You Burn Me Up I’m a Cigarette“, is startling for being so straightforward and unrepresentative even for a record as eclectic as Exposure. Fripp could have been aping the Ramones’ fascination with pre-Beatles pop, but its Chuck Berry riff and double entendre sound as much like a throwback to the Rolling Stones. “I May Not Have Had Enough of Me, But I’ve Had Enough of You” pummels like latter-day Led Zeppelin, playing a serpentine John Paul Jones riff off a thumping Jimmy Page riff as the vocals of Peter Hammill and Terre Roche duel over the top. “Disengage II” stomps along on a 21st-century schizoid lick, which the instrumental “Haaden Two” throttles to a Black Sabbath-paced crawl. Exposure is structured, like David Bowie’s Low, with its first side composed of songs and its second half dominated by mood pieces. The ambient compositions “Water Music I” and “Water Music II” set a sympathetic scene for a recasting of Peter Gabriel’s “Here Comes the Flood“, a previously released song which here is given a sparse arrangement more to Gabriel’s liking. “Urban Landscape” is a self-explanatory work of chilly ambient Frippertronics, while on a similar theme, “Breathless” is an instrumental that combines thick layers of Fripp’s guitars and dense polyrhythms by bassist Tony Levin and drummer Narada Michael Walden. “NYC3” captures another dimension of Fripp’s New York experience. What sounds like another intense duet between Peter Hammill and Terre Roche is actually a sample of a neighbour’s argument that Fripp had recorded through the walls of his Hell’s Kitchen apartment. Demos of Daryl Hall’s vocals for each of Exposure’s songs can be heard on the 2006 album reissue. The album’s conception was, in essence, a collaboration between Fripp, Hall, and lyricist Joanne Walton. Following the battle with Hall’s record company, a ballad that Hall had co-written, “Mary,” was re-recorded with the graceful vocals of Terre Roche. “Chicago” combines a throbbing disco beat, Hall’s bluesy piano, and eerie Frippertronics, and its reworking is given a little extra courtesy of the theatrical chanting of Peter Hammill, whose larger-than-life presence brings a new dimension to Fripp’s catalogue of collaborations. “This thing about collaboration without pre-conceptions: Peter is a remarkable singer, but as in all these situations where there’s a style of English artist where they’re unproduceable. They determine their own situation, nothing can change it. Bowie, Eno, Fripp, Gabriel, (Bryan) Ferry, Hammill – these are the names that spring to mind. No one could normally come along and put Peter Hammill in a context where he would have to work outside his own way of operating, and since from the conceptual point of view my way of operating is not very far removed from his, he could immediately respond to it.” Perhaps no time and place are more eulogised in popular music mythology than New York City in the late 1970s. Really, it makes total sense that the prolific presence of a British progressive rock icon has been buried in its history. A contemporary review of Exposure by the British critic Nick Kent would capture its significance amidst the shift in popular music. “Simply put, Exposure approaches alternative musical contexts, pairings and experiments with a maturity and dexterity that only a dedicated musician could display… He does what he does best — plays guitar and certain other related electronic gadgets — and picks his players very carefully… An example to us all, in fact, it’s the likes of Fripp and Tom Verlaine who are going to make truly new music because they’ve appreciated their art’s traditions, but are also capable of perceiving and developing their own visions. Meanwhile Exposure isn’t just a title, it’s what the record demands. Your ears have been told.” As Robert Fripp bided his time, Gary Numan became an overnight star. He led the Tubeway Army, a cyberpunk band whose 1978 self-titled debut was rereleased after their second album Replicas and its associated lead single “Are Friends Electric” became UK hits. Numan then began a solo career with the 1986 album The Pleasure Principle, featuring the hit singles “Cars” and “Complex“, meaning he had three hit albums and three hit singles in one year. Possessed of a mannered voice and stage presence which when combined with the sight and sound of a bank of synthesizers brought inevitable comparisons to an android, Numan was an unlikely pop star, which contributed to his novel, esoteric appeal. In early appearances on British television, Numan requested that he and the band were lit by stark white light, in contrast to amber and green combination accepted by most acts as standard. “Cars” would become a hit in America the following year, where he would remain a one-hit wonder. To a handful of American critics who were not yet exposed to the furthest reaches of British post-punk, Numan became the face of UK art pop, selling back guitar-based rock with value added. Yet more generally, the music press condescended to Numan as a synthesizer-toting teen idol, although his reputation cannot be taken seriously in light of his extravagant success, a factor which taints critical judgement with resentment. In reviews, he was widely dismissed as a David Bowie clone. Yet his opinion at the time of both Bowie and Brian Eno is revealing. “I’m not too keen on the Bowie Low things. I can’t get much out of them, ideas-wise. I’m more interested in electronics that are playing rhythms.” One interviewer was astonished that Brian Eno had not influenced him. “Everybody told me I’d like Eno, but I never used to like Roxy Music so I never listened to him. So I listened to Eno, and bought, I think, Before and After Science and didn’t like it much. And then I got Music for Films and thought that was brilliant.” The guitars on Replicas run the gamut of glam, punk, and heavy metal riffs. “Down in the Park” meanwhile features a heavy keyboard riff and was covered by both the Foo Fighters and Marilyn Manson. “Down in the Park” and “Are Friends Electric”, both powered by synthesizers, were released as picture disc singles on Beggars Banquet Records, with distribution and marketing support provided by Warner-Elektra-Atlantic. For The Pleasure Principle, Numan forsook guitar playing to work solely on synthesizers, in the same manner as Kraftwerk and the Human League. That latter band would later embody the sound of synthpop with the 1981 hit “Don’t You Want Me” but had emerged from a Sheffield scene that would be very influential on the divergent styles of industrial and techno that had little to do with conventional rock music. The key to The Pleasure Principle‘s success is that it is an album of guitar-less rock music. As with the New York punk band Suicide, the synthesized riffs on tracks such as “Metal”, “M.E.”, and the epic length “Conversation”, which were processed using guitar effects pedals, might feasibly have been played by a heavy rock band. Numan could also have incorporated drum machines into his robotic rock, but he didn’t go so far as Kraftwerk and relied instead upon the organic rhythms of drummer Cedric Sharpley. When a song required a little tenderness, he would augment the heartbeat of pulsing synthesizers with sombre piano and viola courtesy of keyboardist Chris Payne, as on the album’s second single, “Complex”. The combination of keyboard riffs and crisp drumming inverts the big gated drum sound preference among guitar-led post-punk bands like Siouxsie and the Banshees. In tracks like the gliding album opener “Airlane,” the marching album closer “Engineers,” and the signature song “Cars,” Numan’s songs show a self-evident interest in machines, and outside of music, he is an experienced and enthusiastic aviator. He’s also a reluctant futurist. “Most of the songs on The Pleasure Principle are about me and not really about the future at all,” he says. The automobile has long been associated with popular music as a symbiotic object of excitement and freedom. Hollywood films like George Lucas’ American Graffiti (1973) and Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969) have integral rock ‘n’ roll soundtracks and depict urban cruising and cross-country road trips as a means to form bonds between friends and lovers. From its first verse, “Cars” appears to be a love song for the car itself, but while Queen had already recorded the somewhat ludicrous anthem “I’m in Love with My Car“, Numan’s need is not for the freedom it allowed, but the security it gives. Each of The Pleasure Principle’s terse, specific song titles is suggestive less of a pop record than an album of library music. Numan’s particular high regard for Brian Eno’s Music for Films is significant because there are songs on The Pleasure Principle that are reminiscent of soundtrack composition. The most self-evident of these is “Films”, which includes an ominous, repetitive rhythm and eerie, piercing synthesizers which are evocative rather than easy listening. While Music for Films (1978) is an important entry in Eno’s ambient catalogue, another important contribution to electronic music was made by composers such as Delia Derbyshire at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, who most famously composed the theme for the long-running television series Doctor Who. When asked to choose either music, film or television as his preferred form of entertainment, Numan chose television. “It incorporates the others to some degree. It’s the most varied.” The subliminal influence of film, television, and early video game soundtracks is overlooked in the annals of popular music. The resurgence of rock in the 1990s would see the explorations of Robert Fripp and Gary Numan resound in experiments across alternative rock and alternative metal. After raising the bar for new wave with his collaborations, by taking the lead on Exposure, Robert Fripp created a modern guitar rock record which matched the invention of his Frippertronic solos with epic guitar riffs that harkened back to the 1970s sound of King Crimson, and which echoed in the hip-hoppertronics of Rage Against the Machine‘s Tom Morello and the dissonant grunge of Soundgarden‘s Kim Thayil. While the concept of a guitar-less rock band didn’t fully materialise, The Pleasure Principle’s influence was present in the industrial metal of Nine Inch Nails, who covered its songs, and the funk rock of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, whose guitarist John Frusciante’s approached their 2002 album By the Way by “learning all Gary Numan‘s synthesizer parts on the guitar because that was very much in the way that I wanted my guitar playing to be.” Works Cited Tiven, Jon “Robert Fripp: Retiring Fripp“. International Musician & Recording World. June 1975. Retrieved from RocksBackPages.com Needs, K. (1979) “Robert Fripp”. ZigZag. Retrieved from https://www.rocksbackpages.com/Library/Article/robert-fripp Kent, N. (1979) “Robert Fripp: Exposure (Polydor)”. New Musical Express. Retrieved from https://www.rocksbackpages.com/Library/Article/robert-fripp-iexposurei-polydor DiMartino, D. (1980) “The Principal Pleasure Of Being Gary Numan”. Creem. Retrieved from https://www.rocksbackpages.com/Library/Article/the-principal-pleasure-of-being-gary-numan Rose, C. (1979) “Oblique Strategies”. Harpers & Queen. Retrieved from https://www.rocksbackpages.com/Library/Article/oblique-strategies Rambali, P. (1978) “Independents Day Revisited”. New Musical Express. Retrieved from https://www.rocksbackpages.com/Library/Article/independents-day-revisited

Categories: Music

Recommended news

Roses arrive at the Meadowlands Hotel after the final rehearsal

The Sims 4: Best Worlds To Build In

A Heartwarming Reunion: How Community Efforts Led to Finding a Pomeranian Named Butter

Authors

Popular news

How children of European officials went to school in Brussels half a century ago