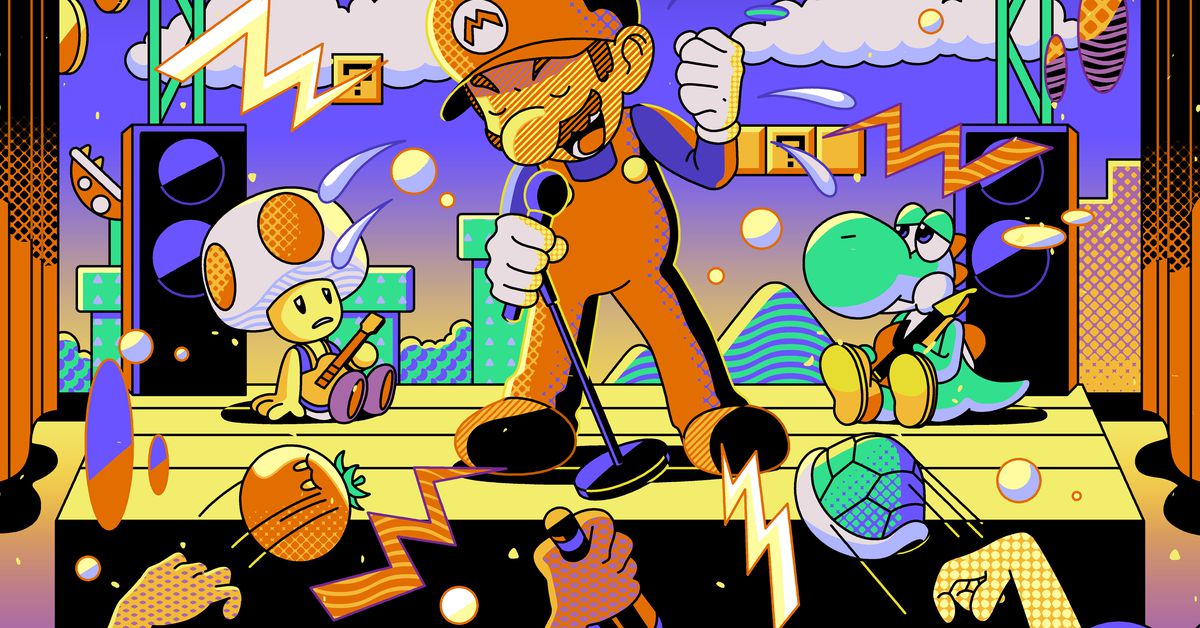

When does video game music get too repetitive?

I enjoy games that make me think, which means I often find myself pausing — not literally pressing pause, but simply staying still — to consider what I need to do next. Those are the moments, like stopping to investigate how I can climb that wall in Ori and the Blind Forest or checking my inventory before heading into the mines in Coral Island, that game soundtracks come into the forefront of my mind. And there are a ton of those moments in any given game. So how do composers make game music that doesn’t, frankly, get annoying? These days, game soundtracks regularly exceed 100 tracks — but players are liable to spend hundreds of hours putzing around massive games like Elden Ring. Even after collective days of playtime — or hours spent trying to grind through a tough level where the music doesn’t change — songs from our favorite games are nostalgic, motivating, thrilling. How? We asked 13 video game composers, who have scored the likes of Hollow Knight, Assassin’s Creed, and Pacific Drive, just that: When writing music for video games, you know going in that the songs will be replayed over and over. What are a few tactics you use, whether they relate to music theory or game design, to make sure players don’t get annoyed with in-game music? Here are their answers. [These interviews were conducted via email and edited for format and clarity.] My general rule is that if I don’t hate myself after obsessively listening to my own music for the purpose of the project, on repeat, in development, then it can’t be that annoying. The ultimate goal is to devise music that provides a balance between the feeling of repetition and variation. If you repeat too much within one loop, that’s only going to get multiplied when each loop occurs, and will therefore become very irritating. On the other hand, if you through-compose inside the loop — that is to say, if you have no repetition and always have it evolving — you may end up with something that is hard to grasp, and the loop point will actually become more obvious, contrary to the intent behind through-composition. Our ears always seek patterns, so we like repetition, but I also think our brains really get off on subtle changes to those repeating patterns. This sort of thing can be found in theme and variation. I like to have easily recognisable and digestible themes, but I also like to take these things and put them in new contexts with variation. It is a tricky balance and I don’t think I always get it right. In any case I believe looping tracks that have a significant amount of interest through the balance of pattern forming and variation is key for the loops to work well. But there is another area which provides a lot of interest for the player, and that is in how the loops are implemented, especially if there [is] more than one mix state for the track. Team Cherry have done a fine job with implementing the three-layer system of the music, where we have one “main” layer, a “sub” layer, and an “action” layer. It is in the constant shift of volume between these three layers as the player moves throughout the world that gives a lot more variation on top of what is already within the composition of the loop. I don’t really have a rule for this. Generally I just try to have melodies overlap each other enough so it kind of becomes a little drone-y. I also like when I get a good feeling from the songs starting over, hopefully feeling more like a progression, rather than a loop. But most of all, if we put the song in the game and realize it’s too repetitive, I just have to revisit it, make it longer, make certain things less pronounced, or change repetitive elements. A large part of this, as simple as it may seem, is to write music that continually moves forward and does not repeat itself. I avoid looping music within the game itself. But, of course, replaying levels or entire games is always encouraged! Music implementation is the key to keeping things from sounding too repetitive. I always work as closely with the developers as possible. Much of this comes from closely collaborating with the audio team; obviously, every game is different. One of the general ideas is using stems to keep things fresh — turning different instruments up and down, not just gameplay dependant but also time-based. The combination of the two, along with a fairly large selection of stems to choose from, can make the music feel like it’s constantly moving forward. This is something I find fascinating and truly one of the things that makes video game music stand out from other music industries. In pop music a lot of work is put towards making the music as instantly gratifying as possible. In film, the music has to fit perfectly with the story and the scene, and even if the music doesn’t play along with the scene, it needs to connect you to the story. For a video game score, we can take many different perspectives. For example, in Warhammer: Vermintide 2 the music approach has me join the Skaven army and so you are thrown into this world that does not feel welcome and can feel quite otherworldly. The music is inspired in a realistic sense of what it would mean to put a Skaven band together in this world. So the music is played in all kinds of unorthodox ways with some mad scientist on the keyboards and some weird homemade instruments for string and percussion-based performances, etc. In many ways, I don’t like the music to only add an emotion that makes you feel what you are supposed to feel here, be it scared, sad, etc. I really like to add something that gives a deeper meaning to it as well. Working to come up with elements from the story or characters that goes beyond what we are seeing. You will still connect the dots, and perhaps you were able to learn something deeper about a character only by the actual music choice. This is an approach that was especially effective in Darksiders 2, where the world of the afterlife accompanies you musically all through your journey. It also worked really well in Freedom Fighters, where, for example, after you blow up a bridge, a huge glorious anthemic Russian choir starts singing acapella. This is the opposite of what people expect, since you are fighting against a Soviet invasion, and it just gives you a huge boost when playing the game. It reminds people of the world out there that you are affecting, instead of just giving you an allied sounding victory moment. So, I feel that scores should be an adventure that the game player or film viewer experiences together with the visuals. It is so important to make that an entertaining part of the game/movie by treating the player or viewer with a lot of respect and making choices that, in order to understand, you need to pay close attention [to]. I don’t believe in the idea of dumbing anything down. You could say I write music for fans of genres. If I write a horror film score, my perspective is to come up with something unique and unusual that will make the score connect to other things inside this universe rather than just a mood of being scared. For example, my dark fantasy horror score for Tumbbad or the opening scene for Assassin’s Creed 2. It portrays and feels very different from what we’re actually seeing and it hints at a huge journey to come. It is delivered in a way that if you’re really paying attention, it’s a huge gain for the story. In a way, it’s made to suck you in, to make you pay attention. I want the viewer or gamer to feel that they are in good hands, that we will take them for a wild ride and that all limitations are gone and you never know what to expect. Perhaps that is why I like working in adventure, fantasy sci-fi, horror, and thrillers so much. I try to work on games and films I myself want to play and watch. A more generic approach might just roll right over your head and you’ll barely notice that moment. You actually only hear the Ezio theme three times in Assassin’s Creed 2; in the opening scene, the scene where Ezio finds his father’s Assassin’s Creed costume, and the end credits, and yet it became the most popular track. At first we thought of adding this track to the execution of Ezio’s father and brothers, but I am so glad we decided against this, since that cue would have been forever connected to that one moment. Instead it’s much more open to interpretation, and [to figure out] exactly why that track sounds the way it does, you have to fill in all those blanks yourself. That makes the music deeper and it makes it special and different for each person that hears it. So everyone can get a different experience out of listening to that music because we are not literally telling you what it is and why it’s there. I also did that type of approach with Borderlands 3, where the main menu music hints at a huge adventure to be had in a world out there that you can go join and you can experience, but for now we’re gonna sit here at the main screen and chill and have some deep feelings. So, There is a world out there waiting for you to experience; that was my philosophy behind that theme. And again, it doesn’t give anything away, so that might be my explanation as to what I was thinking about, but if someone else listens to it, they could have a completely different explanation as to why that music sounds the way it does. I find this fascinating and it creates a depth to the art that we’re creating. For repeated listens I also work towards adding a lot of details in my music with complex harmonies that aim to be listened to over and over, so the second time you hear it you will discover new things, and the third time you hear it you’re still discovering things. And there’s nothing more exciting than writing a 10-minute main title cue, and imagining people thinking it’s just a 30-second loop and they discover the full track and decide to listen to it and then they realize, Oh wow, this music goes on and on. That approach takes me right back to when I was 13, sitting in my room listening to game music. I am fortunate to write for shorter games, so it’s not so much of an issue for me. I’ve never had to compose a cue that’s repeated in a game. I never write wallpaper — if the cue is there, it’s there for a reason. Again, I’ve been really lucky because [The Chinese Room co-founder] Dan Pinchbeck has written such beautiful stories for me to compose to — they have provided the most extraordinary opportunities to write expressive, expansive music. I have two main tricks that I use for repetition. One is sort of deceptively simple, but I always try to write melodies and motifs that get stuck in my head. That’s always a tall order, but much of my writing does happen in my head before I play it into the computer. I think we underestimate the building blocks that happen simply by listening to and digesting music. I’ve listened to so many melodies over the course of my life. Movie scores, TV themes, commercial jingles, game soundtracks… Almost everything in Western media or inspired by it is built out of 12 tones, and yet it all manages to reconfigure in different ways to create the memorable nuggets of music that stick in our head. So when I write, I try to recall those little parts that get stuck in there and use them to create new melodies that feel natural to hum along to. And when you’ve already got it in your head, then a loop doesn’t feel so bad. The second trick is to use some techniques from jazz composition and write the piece like a lead sheet. Play the melody all the way through, and then only keep the chords around. When you go around for another go, you don’t need the melody there because we’ve already heard it. The chord changes are there, and maybe you can include some solos or a vamp or transition to a new section altogether, but when you come back to the melody it suddenly feels less repetitive because we’ve gone on a journey first. Adaptive music is one useful technique that can be used to avoid fatigue. In A Short Hike, each area has three-to-four different sub areas where the instrumentation and feel of the music changes in subtle ways as players move between them. This way, a player can explore that area for a good amount of time and hopefully not get tired of hearing the music. Another technique I try to do when writing is to make contrasting sections, some that are passive and some that are more active. My hope in doing this is that the active sections serve as enjoyable hooks that come up every now and then, while the passive sections are enjoyable but less earworm-y. Ideally, in doing this, players will remember the music later, but won’t get sick of it on repeat listens. It’s a conscious choice of different elements of music like a register. For example, the high register is more tense for the ears, but due to the nature of harmonics, one can be more adventurous with orchestration and let the melody sing more. Another one is the choice of intervals, harmonic rhythm, or the density of counterpoint. There is no ready answer for what works and what does not. After I compose a piece, I loop it for 10 minutes or so while doing other things around the studio. If I’m not bothered by it, it works. A lot of my creative decisions depend on the type of gameplay and how involved the player is at any given moment. Listener fatigue is a very real and important consideration when writing music for games. There are things you can do in both the writing and the implementation to help with it. Variety is key — the most powerful tool you have when it comes to how to fight fatigue is limiting how much the listener hears things, so that when they do hear music, it carries weight. Silence can play a big role. In games like Fez and Hyper Light Drifter we lean heavily on silence to break up the musical moments, and to provide the player with moments of contemplation, palate cleansing, or just moments to have a different feeling. If the game is fun and the player’s preoccupied with landing headshots, the composer gets away with some pretty repetitive stuff… I’m half-joking, but there’s something to be said for the importance of making the music adaptive and making sure it matches the player’s second-to-second experience. If you’re making music for games and the music isn’t adaptive, you’re not utilizing the potential of the medium and you might be in the wrong line of work. But to answer your question more directly, I think it’s simply about playing the game and determining yourself how much time the player will spend in each phase/map/location, and then [producing] music with that in mind. The fact that game music should match/enhance the atmosphere just like in movies goes without saying, but the risk of repetition is unique to games. So if you’re making music for a part of the game where the player may get stuck or hang around for a prolonged amount of time for whatever reason, make sure the music is subtle and/or contains a lot of variation to make sure it doesn’t become grating on the ears. It’s common sense, really. There are many techniques composers themselves can employ, such as limiting the harmonic movement of bass lines for shorter loops, or simply writing longer pieces with lots of textural changes within. But I believe this is better solved in the music’s implementation itself — designers should more carefully decide where music should play, allowing for moments with no music at all and giving sound design the focus. Having a variety of cues at different intensity levels helps a great deal as well, especially if these intensities can be set dynamically through gameplay syncs. I feel that game music needs to be in harmony with the game’s scenery, bosses, and in-game situations, and therefore I try to make sure that the music is not too assertive, all over the place, or too emotional for the player, except in situations where it is necessary to do so in a staged setting. I also feel it is necessary to control the music so that it does not become more emotionally preoccupied than the situation.

Categories: Music

Recommended news

Fabulous Beauty Awards 2024 winners revealed – and you could win EVERYTHING

Fabulous Beauty Awards 2024 winners revealed – and you could win EVERYTHING

Authors

Popular news

How children of European officials went to school in Brussels half a century ago