Birth of the Techno: Juan Atkins on the Early Days of a Dance-Music Revolution

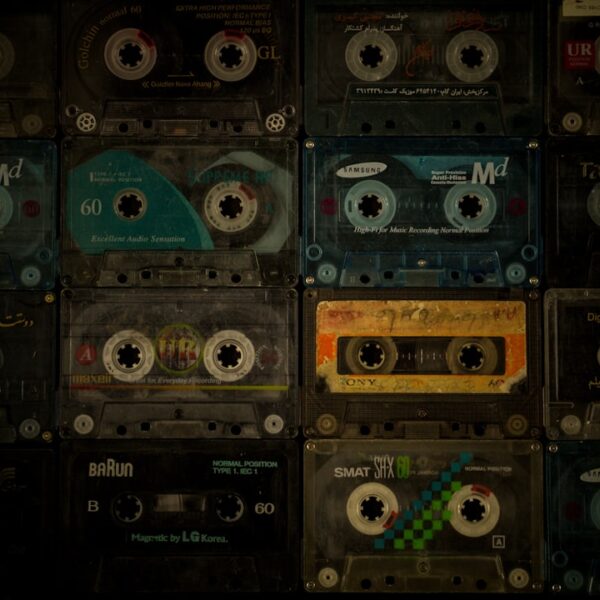

O nce, I was sitting in the apartment of WestBam, Germany’s iconic techno DJ, at Berlin Alexanderplatz, when Juan Atkins’ name came up. Without him, we all would be nothing — that’s how WestBam described him. I was surprised to learn that the two had never met. It was a coincidence that Atkins, whom I’d met earlier, was in town that night. So we spontaneously invited him over, and 20 minutes later, he joined us for dinner. WestBam treated Atkins with extreme respect. I first met Juan Atkins in Berlin, at a party, more than a decade ago. The architect of techno music turned out to be a very easygoing, warmhearted, funny person. Our backgrounds and careers couldn’t be more different. He, the DJ, the son of a drug dealer in Detroit. Me, the journalist and media CEO, born into a sheltered middle-class German family. Despite the differences, we both started out as bass guitarists, we have the same taste in music, and we both wanted to become pop stars when we were kids. But only Atkins succeeded.Over the years, Atkins and I had many conversations about the origins and the development of techno. The more I learned, the more I realized that Atkins’ role is known to some insiders but not enough to the wider public. So one day, I asked Atkins if we could sit together and talk about his upbringing and his contribution to what I call “the birth of the techno,” after Miles Davis’ 1957 album Birth of the Cool. Atkins obliged. These days, he’s busy as ever: He recently relaunched his seminal techno band Cybotron (with the blessing of cofounder Rik Davis) and has a new album, 12, on the way. He’s also planning to release a new single, “Idle,” under his Model 500 alias, on Metroplex Records. A DJ Stingray remix will appear on the B side. On a sunny yet cold day in January, I drove to Detroit’s Green Acres neighborhood, which looks surprisingly boring. Single townhouses on small lots. Most of them built in the very early 20th century, red brick buildings, cozy family homes. Atkins’ house is on a corner, right down the street from where Aretha Franklin used to live. His wife opened the door with a smile: Atkins is getting ready, she tells me; they had a late night yesterday. I ask if I should have a short walk around. Her answer: “No, that’s too dangerous. There are many shootings here. Yesterday they killed a man just across the street. Come in!“ A few minutes later, Atkins showed up, wearing gray joggers, and asked me to join him in his small office. He sat down at his desk, straight-backed, like the boss. Behind him was framed sheet-music of “Amazing Grace.” We opened two bottles of Heineken and began the journey into music history. JUAN ATKINS: All right, the press is here.I would like to start with your first memory of sound.I have a story from when I was in my mother’s womb. My mom told me that I moved in a certain way in her stomach when she played certain songs — and only those songs. So, she noticed I was reacting. Did she tell you which songs?She mostly listened to Motown. That was the Sixties, and I was born in ’62. The first songs I can recall, also after I was born, were mainly Motown stuff. “Cool Jerk,” for example. “Cool Jerk,” and Aretha Franklin. “Respect” and most of her early hits. The Doors’ “Light My Fire,” Martha and the Vandellas’ “Jimmy Mack,” Smokey Robinson and the Miracles’ “Tears of a Clown” and Jimi Hendrix, “Foxy Lady.” Do you have any personal memories of a sound or sounds that impressed you when you were a little kid?I can tell you that the only thing that related to sound for me was music. Was it more melody or more rhythm?I was more into rhythm. My mother told me I used to bat back and forth on the couch like this [demonstrates]. I can even remember that myself, although I don’t know exactly what I was vibing to. I was tiny — couldn’t even walk at the time — but I was moving. Who were your parents?Well, my mom was 15 years old when she had me. My dad was 17. He was actually a barber, but he also worked at Ford Motor Co. for a brief time. But then he actually got locked up when I was two, maybe three years old, for manslaughter. My grandma more or less took over my mother’s role, because my mother was really too young. I’ve got a brother who’s 10 months younger than me, so it was a heavy burden on her. Did your father admit to the crime?Long story short: There was a guy that liked my mother, and he would taunt my father, talk about him in the street. My dad had just got this car, and it was brand new. I guess the other guy was somewhat jealous, and they were riding down what people called “The Strip” [Visger Road], which divided the boroughs of Ecorse and River Rouge in southwest Detroit. It had a barbecue restaurant where everybody hung out. My dad was riding down the strip and this guy was riding behind him, taunting him, signaling him and calling him names and stuff. And so, my dad decided he had had enough. His friend handed him a gun and said, “Hey, go and take care of it.” And he went and took care of it in broad daylight. I think he got sentenced to [eight-to-15] years for manslaughter. Is your father still alive?Yeah, he’s serving a life sentence right now. He did something bad again. What was it this time?This time he got a life sentence for murder. My father was a drug kingpin. He was a drug dealer. It sounds like a comandplicated childhood. Was there any happiness?I didn’t have any doubts about the love my parents and my grandparents had for me. That was a given, something you could count on?I don’t know what it was. It was something I felt, but I never said it to myself, and I never questioned my parents’ love for me. Do you visit your father in jail from time to time?Yeah, we visit from time to time. He’s been in jail since I graduated high school. Serving this life sentence. What I do remember is that when my father got out of jail after his first sentence, I was nine years old, because he gave me an electric guitar for my 10th birthday. Because you wanted a guitar?No, but I was always musically inclined. It was something everybody kind of noticed. He’d get gifts for my younger brother Aaron and me at Christmas, and I would talk my brother into getting musical instruments as a gift so that I could use them too. He didn’t really want them, but I talked him into getting a set of drums one year. My first instrument was an electric guitar. It was a Slingerland, and the case was the amplifier. Was your father very musical?He played alto saxophone. And he taught me a little bit about it. But you spent most of the time with your grandmother. To which degree did she influence you musically?I got much more musical inspiration from my grandma because she owned a Hammond B3 organ. When we went to live with her, she played on it. Mainly the boogie-woogie. And I used to play around with this organ. Did you practice a lot? The organ and the guitar?The guitar came way after the organ, but I was never really disciplined to play like I should have or could have, you know. What was the first song you tried to emulate?A Sly and the Family Stone song, because I was playing bass, too. And that was a classic bass line, boom, ba boom boom boom … also Eddie Kendricks’ “Keep on Truckin’.” I played the drums along with those records by ear. I taught myself to play various instruments “by ear,” as they say. You told me that your biggest musical influence to this day is James Brown?James Brown, P-Funk, and Motown to a certain degree. Motown mainly because that’s what my parents were listening to. James Brown is one of the most influential musicians of all time. The most important thing, in my opinion, was that he transformed instruments that were not supposed to be part of the rhythm section into percussion instruments.Right. James Brown is the godfather of funk music, which I basically grew up with and is most influential in my music production. In the James Brown biopic, there’s a notable scene where Brown, while rehearsing a new song, asks his brass section what instruments they’re playing. When they respond with “saxophone,” “trombone,” and “trumpet,” Brown repeatedly corrects them, saying, “No, you’re playing drums.” For me this is a crucial and very telling scene. All the players in the brass section were trained to play in a rhythmic way. Like percussion instruments or the guitar. And this is exactly what, years later, led to electronic music and techno. It’s all about rhythm. Rhythm is in the center.Exactly. How did the bass as an instrument come into your life?Actually, my grandmother bought it. Did she already realize at that point that you were particularly talented and wanted to support you? Yeah, she was always supporting me. She bought me my first synthesizer as well. It was a Korg MS-10. How old were you at the time?Fourteen or 15. Were you planning to become a musician at that point?I always knew, already in the womb I think, that not only did I want to become a musician, I wanted to become a pop star. A pop star?Yeah. It’s a calling. Something I organically felt that I was put on this planet to do, or supposed to do. What was your favorite instrument? Keyboard, drums, guitar, or bass?Well, in terms of sound, the bass was always what stood out to me. As you know, I used to be a bass guitarist as well. For me it was the combination of rhythm and the deep sound. The physical experience. The sound and vibrations that you feel with your whole body. Why the bass for you?Because you could play the bass on the synth. And then that became my obsession. When I discovered the synthesizer, my whole horizon, my whole world opened up. So, as a boy of 14 or 15, you already knew you wanted to be a musician. Did you play in bands?Yeah, we had what you call garage bands. I don’t know if you had this when you were a kid in Germany, but you could walk through the neighborhood and there’d be a group of guys somewhere on some block playing in their garage. One of my best friends at the time was Jimmy Smith, and he was a bassist. We got together to play. Of course, I couldn’t play bass because he was playing it. So, I played drums or whatever. Or I was on the guitar, he was on bass and a guy around the block was on drums. The instrument did’’t matter to me. I didn’t discriminate one instrument against the other. More the attitude of a future composer and DJ than that of a pop star. DJ wasn’t really on my radar during this time. Mixing records and mobile DJs had not yet been invented. Basically, I wanted to be Sly Stone with a new Juan Atkins twist. So music and only music. Any interest in school?Music and only music was always my main focus. However, I always got good grades in school, even though I was just a bad kid. I was just mischievous. I was taking kids’ lunch money from them. I got into my share of fights, but I never got beaten up. I was smart. It wasn’t strength; I just knew when to punch and how to punch. I knew what move to make and what time to grab somebody. I was smart at keeping myself safe. Was there a teacher who influenced you in any way? Someone who was inspiring or had love for music?Yeah. I took a course called Future Studies in high school. And the reference manual for that class was Future Shock by Alvin Toffler. That was the book that took my mind into technology. And why was it so important for you?Because it was like science fiction to me. The instructor was called Mr. Fielder, I think, and he was cool. He was like a hippie. By taking his class I learned about the techno-rebels [a phrase of Toffler’s]. Toffler´s second book was The Third Wave, which is where I learned about the metropolitan complex — metro complex, which later evolved into metroplex. So, in a way you could say that Toffler’s work is the reason why you later called the music you composed techno and your label Metroplex?Yeah, definitely, it was straight from Toffler. The label Metroplex is short for metro complex. And a metro complex is the merging of two cities, like the Dallas-Forth Worth metroplex. Eventually, Detroit and Chicago will become a metroplex, if it’s not already. When did you then develop serious ambitions to become a musician, a producer? Or even a DJ?When my grandma bought me that synthesizer, I saw I had the ability. As a Black kid living in Belleville [a suburb of Detroit where Atkins moved as a teen], it was like the next person who played any type of instrument lived like 10 or 15 miles away from me. You know, it wasn’t like I could just go around the block and hook up with a good bass player or a drummer. So, I had to figure out a way to do all this stuff by myself. And what the synth allows you to do is make all these different sounds to the point where you could almost be a band. But the thing about it was, it was all electronic. I could even make drum sounds off the synth. With a little bit of white noise, and pink noise, turn the filter down a little bit and you got a kick drum. So that’s how I started making my own tracks at home. When my father got out in ’72, ’73, we lived for a stint at my grandma’s hotel with him. That’s where I did most of the Hammond B3 organ stuff. After that we moved in with my father, who had bought by now a house on the northwest side. It was right down the street from here. That was the time when I had my bass guitar. It was a Rickenbacker copy; it wasn’t real, but I liked the look of it. It was really rock & roll. During that time, I would be around the house doing make-believe concerts and jumping around with this Rickenbacker. I would put Noxzema on my face; it made your face look like it had white chalk on it, basically. My father used to ride motorcycles, so I would put on his helmet. He had these real futuristic-looking motorcycle helmets that are a bit like a shield here and cover your whole face. So, I would put this helmet on like I was KISS or some rock- & roller. The Midnight Special concert show was on TV at the time. And another network, ABC, had In Concert. They would film concerts and all my favorite stars were on there, like Parliament-Funkadelic. Sometimes they would have on Sly and the Family Stone. So, there was no professional approach and no idea of Cybotron, the electro group you formed in 1980?This was nothing near professional; at this stage I was just developing. How did you meet Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson, two friends who are often mentioned when it comes to the creation of techno?Derrick and Kevin were not into music at all — they were playing football. They were in my brother’s class, which was two years under me, so they were actually his friends. Somehow me and Derrick became friends, and I would beat him in chess or whatever. But one time I was sitting on the porch playing my bass guitar. I didn’t have an amp or nothing, but you could still hear it. He was riding down the road on his bike, and he came up and started talking to me. We kind of became friends, but it wasn’t on a musical thing at all. Derrick and Kevin only started getting interested in music after we, Juan Atkins and Rik Davis as Cybotron, released “Alleys of Your Mind” [in] early 1981 on our own Deep Space Records label. Rik Davis was a fellow electronic musician I met in class at college. I would bring my home demo recordings to class and everyone was blown away by them, including Rik, who then invited me to his home studio to jam. He had his studio situated in the bedroom of a two bedroom apartment on the Eastern Michigan University campus. It was like walking into the cockpit of a spaceship. I brought my Korg MS-10 synthesizer, and we proceeded to jam. Our first finished piece we called “Cosmic Raindance,” which wound up being the B side of “Alleys of Your Mind.” When you say released …We actually made a record and put it out. That was my first professional record, and it wasn’t with a record company. That was the moment when Cybortron was started?Yes, Rik and I came up with the name Cybotron — it’s a hybrid of the words cyborg and cyclotron, a man-machine and a particle accelerator. That record with Rik Davis was all electronic. But by then you were already aware of the music of Kraftwerk.Here’s the thing about Kraftwerk: We have to go back to the Electrifying Mojo, a very iconic DJ who more or less had the city in the palm of his hand — musically. He was an ex-Vietnam radio DJ personality who appeared on FM radio station in the spring of 1977, which essentially began as a gospel station. The DJs could essentially play whatever they wanted. And Mojo, as we called him for short, had the best and most eclectic variety of music from James Brown to Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix to Peter Frampton, Parliament-Funkadelic to Kraftwerk to Prince. Mojo captured the imagination of the youth of Detroit before rap and hip-hop. Parliament-Funkadelic and James Brown were deeply rooted in rhythm & blues and funk music, while Kraftwerk was very white music.The thing with Kraftwerk is that it was precise and regimented, and that was the difference. My music then was very loose and organic. Still all electronic, but it wasn’t as precise and regimented as Kraftwerk. It was basically very regular on the beat. Not groovy at all.But Kraftwerk told me their influence was James Brown. James Brown again? Wow! I didn’t know. That’s really interesting because Kraftwerk is so ungroovy.Electrifying Mojo on radio — that was the first time that I heard “The Robots” by Kraftwerk. It froze me in my tracks, man. It was like the best, baddest shit I’d ever heard. You know what I’m saying? And I was making music by this time. I didn’t have anything released yet. This was around 1979, 1980. I was making these demos while I was still in high school. I wish I still had them. I’ve lost the cassette tapes over the years with these early songs that were all drum drops and me playing synth over it. I was amazed at how the music sounded like what I was doing but more precise. And the difference was that they were on the radio, and I wasn’t out on the radio at that time. A lot of people thought that I listened to Kraftwerk and then started doing what I was doing, but it was basically parallel. So, Kraftwerk reminded you of what you were doing, but they had better equipment, more professional resources. Is it fair to say that it also felt a bit like a confirmation that you were on the right track?Yeah, and I must admit that that regimented sound was an influence. By the time I came out with “Alleys of Your Mind,” there was definitely a Kraftwerk influence there. Except Kraftwerk weren’t calling their music techno, while I obviously was calling my music techno. When did you call it techno for the first time?When “Alleys of Your Mind” came out in 1981. And why did you call it techno?Because of my high school course in Future Studies. Toffler was talking about transcending from an industrial society to a technological society. “Techno” is short for “technology,” of course, and it just seemed logical to say this music is techno music, or technology music, because it’s based on machines born out of the technological revolution. So, there was this intellectual influence from Toffler and musically from Kraftwerk and James Brown, and of course your own romances with P-Funk. Those are the main ingredients?Here’s the thing. Even before Kraftwerk, there were records like “Flash Light,” like “One Nation Under a Groove,” that were mostly electronic. “Flash Light,” by Funkadelic, was closest to my sound. As a matter of fact, if I had to point to a direct influence, I’d have to say “Flash Light.” Would you say that 1981 — the year you released “Alleys of Your Mind” — was actually the year of the “birth of the techno”?Yeah, it was a smash hit in Detroit. That’s when I learned I could put a record out. At that time, I thought I had to go to a major company. Then I came across a book called Make & Sell Your Own Record by this author named Diane Rapaport. When I met Rik Davis, he had this book as well. Rik had a lot of literature, and with me and him it was destiny — like we were supposed to meet. Looking at the Belleville Three: I’d like to understand the magic of that trio. Kevin Saunderson and Derrick May are always mentioned in connection with the creation of Detroit techno. What was their role compared to yours?Long story short, Derrick was my best friend basically my senior year in Belleville High School. So going back to when we released “Alleys of Your Mind,” Rik Davis was my partner as Cybotron. Derrick introduced us to Mojo, but Derrick wasn’t a musician. When we released this record, and Mojo started playing it, we were all engulfed by Mojo. Everybody listened to Mojo at night and so, when Mojo played “Alleys of Your Mind,” I more or less became an instant celebrity in Detroit. So, people were hanging around me, and Kevin and Derrick were my friends. You know, we’d go to a party and all the girls wanted to talk to me because I was Cybotron. Derrick and Kevin wanted that too. They were athletes, they played high school football. Eventually, as we were hanging out together, [music] kind of rubbed off on him. Kevin was Derrick’s friend. Derrick’s parents moved to Chicago in his senior year in high school, so Derrick had to live with Kevin to finish high school, which was in Belleville. This was right at the time when “Alleys of Your Mind” was being heard on the radio, and so whatever I did with Derrick, Derrick transferred it to Kevin. And this was also the same time we started spinning records and stuff together. That’s basically how our kind of thing got started. We were doing DJ parties and at the same time there was “Alleys of Your Mind,” which we only put out on 45 RPM. A DJ party at that time basically meant putting records in the turntable, not mixing in a sophisticated way, right?Basically, yeah, vinyl records, not tracks. That came about with mixing, and mixing came about in the disco era. Sampling came later, scratching came later.Scratching was at the same time as mixing. Scratching records was all out of New York. New York was responsible for mixing, blending records on beat. Did Detroit have a club scene in the early Eighties?Disco music was the soundtrack for the gay scene. Gay clubs had been around forever, so that was the music that was being played there. Some disco records crossed over to R&B and vice versa. Like Cameo. Cameo was a funk band, but they made a record called “I Just Want To Be.” That was one of my favorite records, but it was basically a disco record. A lot of R&B groups were trying to come out with a disco record. At the time there were fraternity and sorority parties at college, they called them icebreakers. They would hire us for these parties, along with other DJs. So, on the one hand you were the musical spearhead for electronic music with Cybotron and your own releases. And on the other hand you became a kind of DJ team with Kevin and Derrick, putting that music into the high school world — the local heroes for DJing at these parties?When the clubs came in, the DJs started becoming famous. But back then a DJ just played records, like a radio DJ. Who was the first real DJ superstar?Well, the first DJ — club DJ, not radio DJ — that I recognize was a DJ called Ken Collier. He was a gay DJ and, like I said, this whole disco thing, the whole mixing thing came out in the gay community. What was your ambition at that time? You were a generalist, a kind of producer, then you increasingly became the inventor of a new style of music. You were also a DJ, gradually transforming the role. Did you develop any specific ambition in relation to that?No. The DJ’ing and a lot of this stuff happened organically. There was never a blueprint to it; nobody knew what the hell was gonna happen next. We were just some kids doing what was fun. Having technology propel our ambitions or make it easier. You know what I’m saying? It was like it went hand in hand. But it wasn’t like somebody sat down and said, “OK, we’ll use the synthesizer to make this type of drum sound, and then we’re gonna play it at the club.” Nobody was planning. Could you describe the atmosphere, the vibe, and also the popularity of the music here in Detroit that we now call techno? It was loved by a crowd but of course far from mainstream. Well, the term “techno” got exploited. I mean, even now, techno in Germany is different from techno in Spain. Here in Detroit everybody loved the music. Nobody knew that it was techno music. Especially the Black kids in Detroit. All they knew was that this was a new sound. And whatever it was, whatever the frequency makeup was, it just pushed a button somewhere. When it got to Europe, Europe had to give it some kind of title. Tell me the Berlin story. Who called? The first gig you had at the club Tresor was in ’91, is that right?Well, there was a stop before Berlin. The U.K. was where we started dabbling in international affairs. It jumped off into continental Europe from our trips to London, actually to northern England and the Midlands … Neil Rushton managed me, Derrick, and Kevin at one time. And it was him who made the Virgin Records deal with Richard Branson. They released the first Detroit record, and they called it “techno.” Neil eventually got introduced to me and Kevin Saunderson, Santonio Echols, Blake Baxter, Eddie Fowlkes, James Pennington, Art Forrest, Thomas Barnett, and other people. And he got us together with Virgin Records. The record came out and they were going to call it the House Sound of Detroit. And then I put my record on there, called “Techno Music.” And they changed the name to “the Techno Sound of Detroit” [1988’s Techno! The New Dance Sound of Detroit] And that’s how the Detroit boys got rolled out into Europe. Of course, a lot of people caught wind of it. In Belgium, R&S Records caught wind of it, and Dimitri Hegemann of the Tresor in Berlin. How did you get to know Dimitri?There used to be a conference in America called the New Music Seminar. They used to hold it every year in New York. All the dance music people would go to the conference every year. And Dimitri was there one time. I had heard about the Tresor. Dimitri had put out the Der Klang der Familie record, and he was there promoting it. So, the Tresor club’s reputation preceded itself. I think one of the first DJs to play at Tresor was Jeff Mills. Tresor was licensing music from Detroit. It was kind of a fad for a minute. Do you remember the first night at Tresor? Can you describe it a little?I played with Jeff Mills. It was in the basement. It was surreal, blue white neon. That’s what I remember. Hard to describe into words. So, everybody wanted to play at Tresor. Because the description was that it was like heavy, banging, crowded, with people going for it. Was that an important step for your career?Definitely — into Europe. I mean, if you went to continental Europe, that was one of the first stops at that time. And how long did you play the first set?An hour and a half. And did it go down well with people?Yeah, it was flawless. Did you prepare in a particular way for it?No. The funny thing about that night is that I lost the records I had at the airport. I had to buy records from Hard Wax. I spent the whole evening buying records that I was going to play at Tresor that night from Hard Wax. So that was kind of crazy. And when did you realize that this thing we call techno was really becoming a global success?When I played in London. The first time I played in London was at a film studio — capacity 5,000. So, there were 5,000 kids in this place, right? Me and one of the technicians were the only two Black guys. That was something I’d never seen before and couldn’t even fathom — that I would be playing music for 5,000 white kids. And they were just loving it. You know? And that’s something that I could never have fathomed in America, as a matter of fact. That really felt like a cultural shock. It was definitely a lightbulb moment. And that was when I realized that this music was bigger than I thought it was. How about Berghain in today’s Berlin? It’s the iconic Berlin techno club. A global brand. Why don’t you play there?Because I play Tresor. It’s politics, definitely politics. I actually did play Berghain once — no, the Panorama Bar [a smaller upstairs space]. I played twice at Panorama Bar. But that was an exception. You have to decide. Either Tresor or Berghain. It’s interesting that there’s so much politics. It’s all about territories.It was crazy. It seemed to me that, if you played a set at Tresor, they would want to bring you to Berghain and vice versa. If Detroit is the birth city of techno, then Berlin is the capital of techno.This is up for discussion. Isn’t the birthplace and the capital the same thing? Let’s talk a little bit about technology. How did technology change techno music and the life of a techno DJ? When you started, it was vinyl records that you put on the turntables. Then it moved more and more to CD and modern technology to help mix and synchronize the beats and so on. Right up to the situation today, where a DJ usually shows up with a laptop or a stick.Well, techno is technology right? There would be no techno music without technology. But that’s definitely good when you get older, because it’s kind of hard to carry these big, crazy records. I can remember the time before they even put wheels on record boxes. You had to literally pick up the record box, and a lot of them were made out of steel cases. I remember, oh, my God, playing one place where I had to walk from the train station to the club carrying two record boxes. That gig was the hardest thing I ever did in my life, so I welcome the progress. Apart from carrying the heavy records in boxes, is the life of a DJ today much easier artistically?It’s easier because you have access to hundreds or thousands of records at the touch of a button. The vinyl thing just looks cool. But you know, it has so many disadvantages. The most embarrassing thing is when the record plays out before you can get the next record on. Yeah, man, that’s embarrassing. And if you miss the synchronization of a beat, too. Today, there is no risk because you have the technology. It’s done automatically by auto sync.But real DJs kind of look down on using auto sync. It’s like, “OK, you can play records on the CDJ or laptop, but at least blend the records yourself.” And would you say that the degree of spontaneity is lower today?No, I think it’s increased, because it’s easier. I mean, you can just search, and you’ve got a choice between thousands and thousands of records instead of what’s just in your record box. I know DJs who still play only vinyl, but man, that dude needs three people to carry all his boxes. He literally carries his whole collection to the club. How political is techno? Is it a political movement, or is it apolitical?From my side, I don’t dive into the politics. But I’d be naive to think that politics aren’t there. But it’s nothing that I like to partake in. Would you agree that indirectly it is political because it’s a movement of freedom, of tolerance, of a very inclusive lifestyle? The Love Parade, the festival in Germany, was even seen to be a political demonstration, which I never believed. But it had an indirect political impact, you might say.I like to think it’s deeper than politics. Well, it’s universal. Music is vibrations. And there are frequencies that alter your cellular makeup. I can send a 432 Hertz wave to you, and certain cells in your body will react to it, you know? And so therefore, I think, even though I might not know the intricacy of the frequency, or what frequencies have what effect, I do know that sometimes you have to be spontaneous and just go with the flow of the universe. There used to be a saying, “think long, think wrong,” you know? You could probably see this when I’m playing — I feel a synergy with the people that I’m playing for. And it’s more to me than playing certain places or certain songs, or a certain set for political reasons. Could you describe the most defining elements of good techno music?The synth is the basic parameter or the basic tool for the creation of techno music because it’s electronic. It’s not an acoustic guitar, it’s not a horn. You won’t usually find any acoustic essence in techno music. It’s basically music born out of technological advancements, technological gear. Does techno have a message?The future! Toffler again.Not really. Toffler doesn’t have an exclusive on the future. The future is just simply the future. Looking back to the last 40 years, is there anything that you would have done differently, anything you missed … that you think you should have done?Well, I’m human. I do know that much, I think [laughs]. And I’ve made mistakes that, if I had a chance to fix some things, I probably wouldn’t have done them a second time around. Anything specific?You can only go to the amusement park and ride the roller coaster so many times, you know. So maybe I would have ridden that roller coaster one or two times less. In a figure of speech. Riding the roller coaster doesn’t do anything but give you an instant high. What’s the connection between drugs and techno for you?Well, you know, my father was a drug dealer, for God’s sake. So it was kind of unavoidable. Although I’ve never used heroin or pills or stuff like that. I’ve dabbled with cocaine. And had I had a chance to go back before I experimented with that, I probably wouldn’t have done as much as I did. Do you see any necessity in the coexistence of drugs and techno, or do you think you could be a great DJ without it? Did drugs make your playing better or worse?Let me flip it for a minute. Does that Heineken you’re drinking right now make this a better interview? I mean, nobody can say. You could say that the effect of techno music is very euphoric. You could say, the music does it, you don’t need the drugs. Music is the drug. I don’t think there’s any outside substance, especially a mind-altering substance that will help make me better. Do you ever go to a party and listen to other DJs, just enjoying the music without any professional thoughts or any professional involvement? Just dance and go with the flow?Yes! I mean, listening to other DJs is good for you. Good DJs in particular are always an inspiration for a DJ. I learn a lot of things to enhance my craft from other DJs. What distinguishes a great DJ from a mediocre DJ?A great DJ is a leader. A mediocre DJ is a follower. You said the most important reason to be into techno music is the future.Yeah, it’s progress, it’s future, it’s development. Any idea what the future of techno music will look like? How techno is going to sound and be?Like nothing we ever heard. And there is no way to forecast that because we ain’t heard it yet. That’s what I try in DJ’ing and making music and presenting music. The public attention span is pretty short, and people are always interested in what’s next. Not so much what happened yesterday. Not so much what’s happening right now. But what’s next? If we look back to the last 100 years of music history and recorded music history, we see a trend towards dematerialization. It started with these old heavy records 100 years ago, then the vinyl records were lighter. Then they got smaller as singles. And then you had CDs that were even smaller and lighter. Then you had the MP3 players — smaller and smaller. And then you had the thumb drive. Now you have everything on your mobile phone. A chip. Almost nothing. So, there’s a constant line of dematerialization. Can you imagine music one day becoming completely immaterial?I think music will always be there, but how it’s presented will definitely change. Or how you access music, or how it’s brought to the masses. What role will artificial intelligence play in that context?I don’t know. There might be a day where you could just say, “Hey, I want a four-on-the-floor beat with a bassline in the key of B. Doing about this scale.” And just speak it and it will arrive, right? Could you imagine artificial intelligence being able to replace the composer, the producer and the DJ?That means replacing humanity, right? Or merging humanity with artificial intelligence?I don’t know. But you have created music where humans, based on sophisticated technology, have reached a new level. The use of technology has improved your music.But it still needs a human to push it. I think the source is human. And this leads to my latest Cybotron single called “Maintain.” Mathias Döpfner is a journalist and CEO of the Berlin based digital publisher Axel Springer (owner of the US media brands Politico, Business Insider and Morning Brew). He is also a member of the Board of Directors of Warner Music Group and Netflix.

Categories: Music

Recommended news

CBS News and Stations introduces new editorial leadership team

Lookfantastic beauty advent calendar 2024 revealed and this is the date it is available to pre-order

Authors

Popular news

How children of European officials went to school in Brussels half a century ago